Lantana weed genomics: supporting improved biocontrol

A national-scale study of lantana population genomic variation helps biocontrol programs achieve optimal outcomes.

This project delivered a population genomic study of lantana across multiple continents and revealed unprecedented insight into the weed complex’s genetic composition and ancestry.

Lantana (Lantana camara L sensu lato): biocontrol in an invasive species complex

Lantana is among the world’s worst weeds, and is a weed of national significance in Australia, with substantial economic and environmental impacts.

Since 1902, 44 biocontrol agents have been released in 33 countries to control lantana, with mixed success.

Because biocontrol success hinges on how well-matched (i.e. co-evolved) the control agent is to the weed, biocontrol efforts have been hindered by lantana’s complicated and unresolved identity. The invasive lantana complex is a genetic melting pot of several closely related species, and agents collected and released to date are not necessarily adapted to all the weedy forms. Thus, solving the problem of weed identity and provenance will allow untapped potential in lantana biocontrol to be realised, by matching the weeds to the agents best adapted to control them.

Weed population genomic analysis reveals distinct lantana sub-lineages

Invasive lantana consists of several divergent sub-lineages, and gene flow among them is limited, consistent with the notion that multiple species have contributed to forming the weed complex. It is thus counterproductive to think of lantana as a single homogeneous species, with more accurate identification expected to facilitate better management. Two widespread sub-lineages are estimated to comprise at least half of the populations in Australia; these correspond broadly with the “Common Pink” and “Common Pink-Edged Red” varietes described by Smith & Smith (1982). The common pink variety is genetically most similar to native-range plants sampled from southern Brazil, while the pink-edged red variety is most similar to plants from Mexico. Certain biocontrol agents are variety-specific, damaging their preferred host variety while failing to establish on other varieties.

This research was supported by the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry via the Established Pest Animals and Weeds Management Pipeline Program

How to identify varieties of lantana in Australia

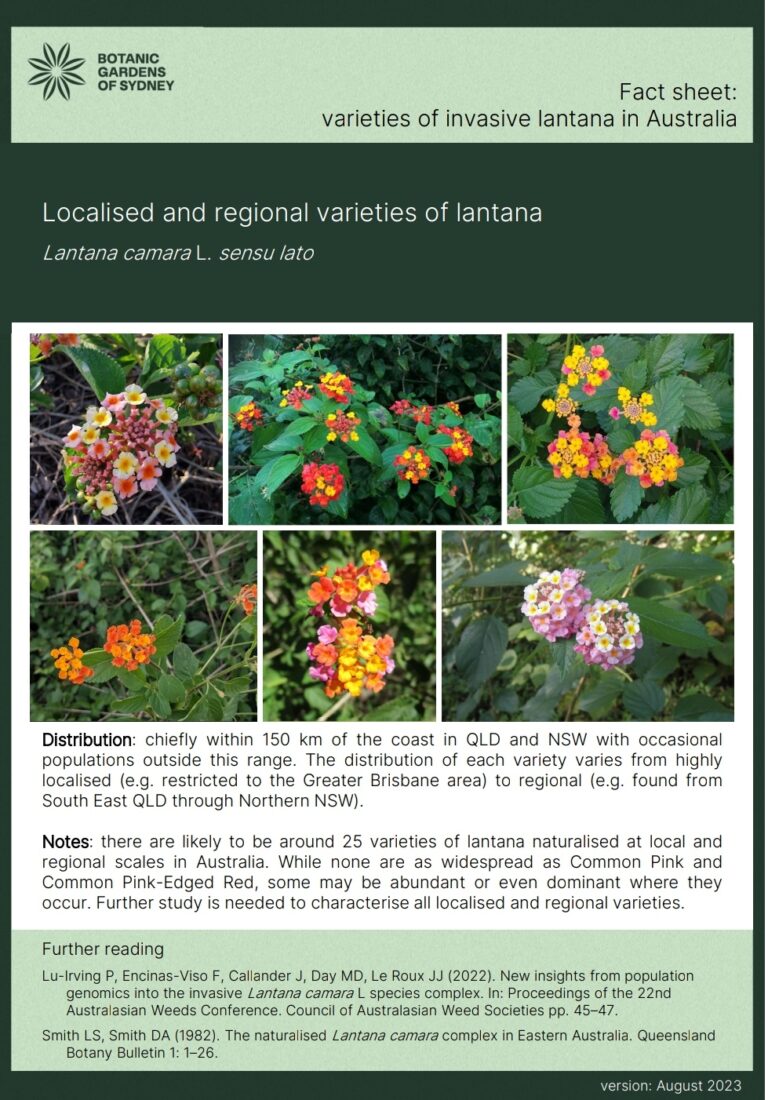

In addition to the two main lantana varieties “Common Pink” and “Common Pink-Edged Red”, numerous other varieties are distributed throughout Australia. While none are as widespread as the two main varieties, they may be regionally or locally abundant. The localised and uncommon varieties may represent horticulturally-bred garden escapes, and/or hybrids formed by spontaneous crossbreeding among varieties in the wild.

Flower colour is an eye-catching and distinctive trait in lantana, but it cannot be relied on to indicate which sub-lineage a plant belongs to.

For example, while “Common Pink” always has pink flowers, not all pink-flowered plants belong to this variety, and the same is true for “Common Pink-Edged Red”.

While flower colour alone is insufficient for identification, examination of all features of the plant (such as location, stems, and leaves) can yield more clues. Even so, plants with different genetic backgrounds can sometimes be almost impossible to distinguish.

Genotyping the plant by sequencing its DNA is a reliable way to identify it (and may in some cases be the only reliable way).

Further detailed study is required to produce a comprehensive taxonomic revision of lantana in Australia, with particular focus at regional scales in Queensland and northern New South Wales, where most of the variation in the weeds is concentrated.

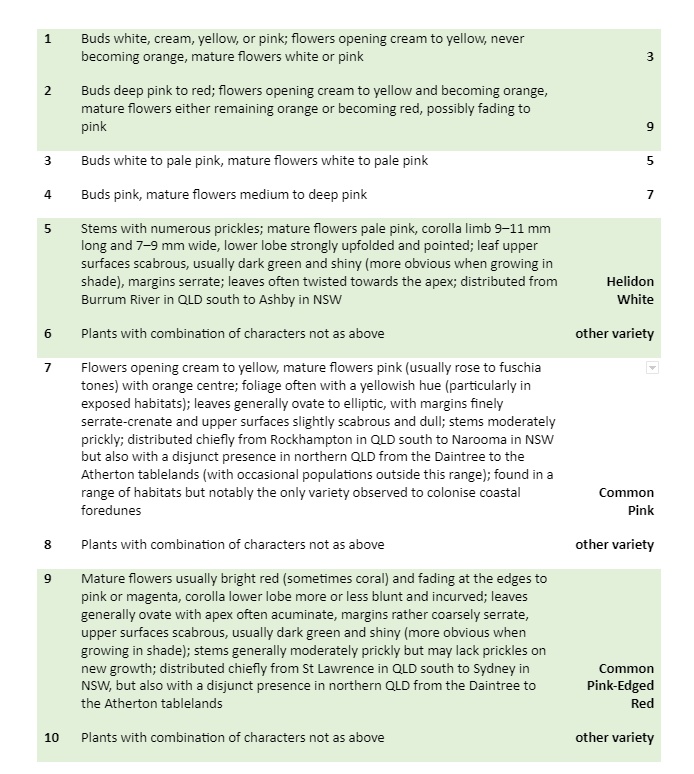

In the meantime, we offer revised descriptions of common pink and common PER following Smith & Smith (1982), and a draft identification key that aims to distinguish these two major varieties from other weed forms.

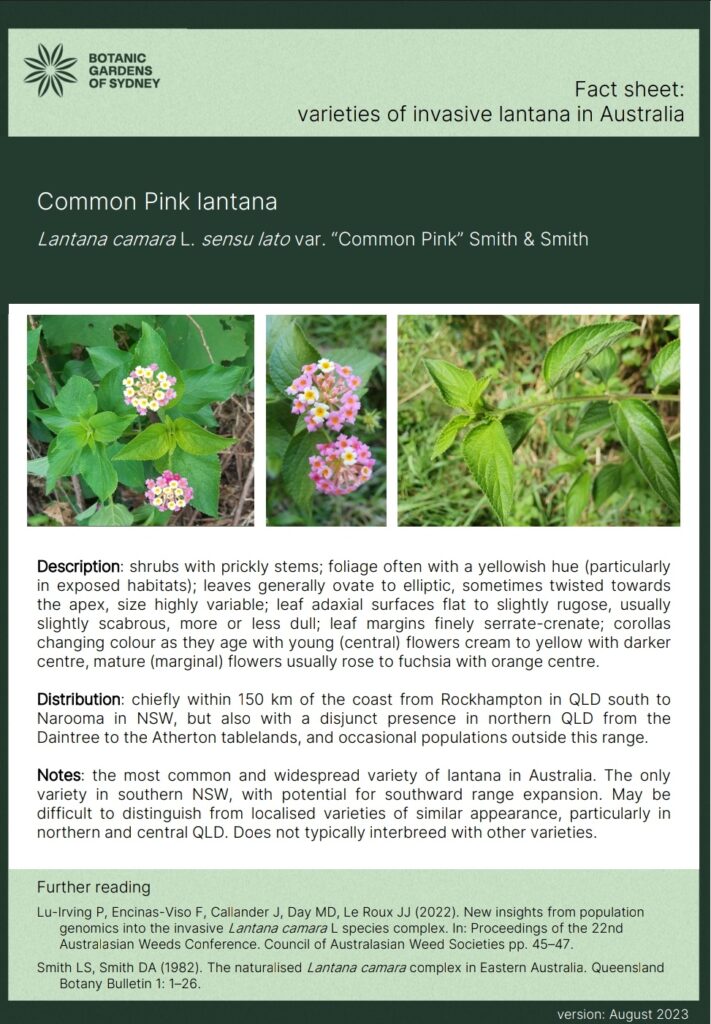

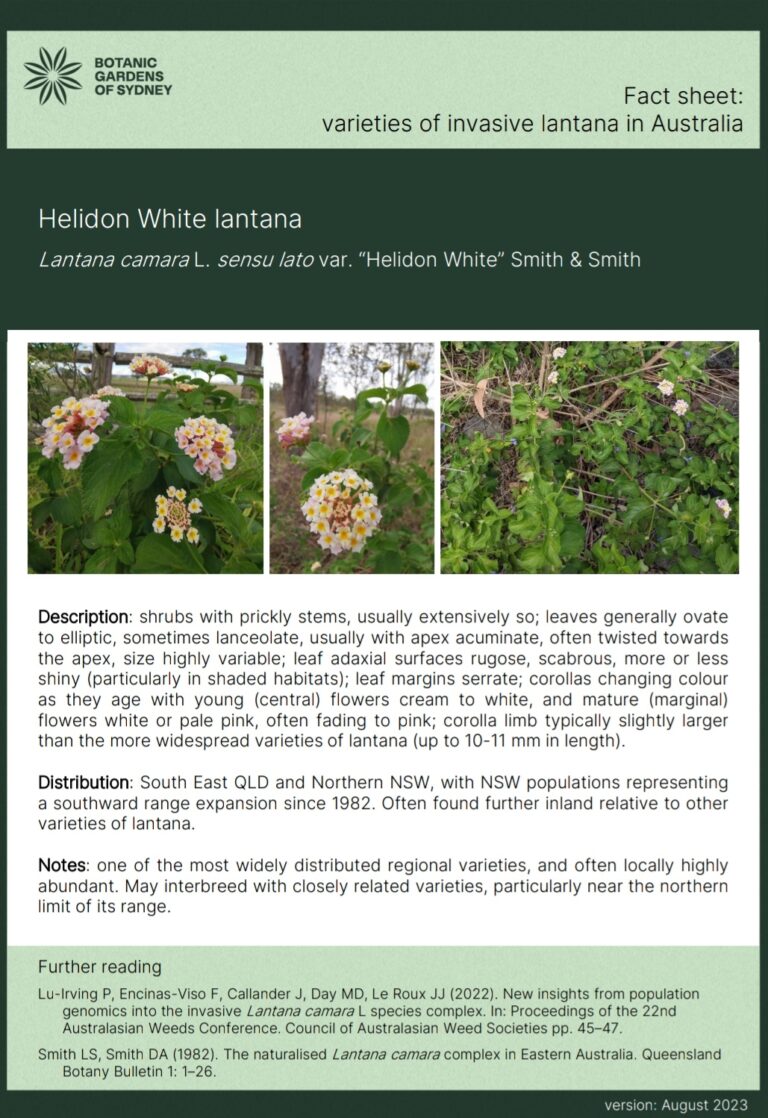

Lantana camara L sensu lato var. “Common Pink”

Revised description following Smith & Smith 1982

Shrubs with prickly stems; foliage often with a yellowish hue (particularly in exposed habitats); leaves generally ovate to elliptic, sometimes twisted towards the apex, size highly variable; leaf upper surfaces flat to slightly rugose, usually slightly scabrous, more or less dull; leaf margins finely serrate-crenate; corollas changing colour as they age with young (central) flowers cream to yellow with darker centre, mature (marginal) flowers usually rose to fuschia with orange centre; distributed chiefly within 150 km of the coast from Rockhampton in QLD south to Narooma in NSW but also with a disjunct presence in northern QLD from the Daintree to the Atherton tablelands.

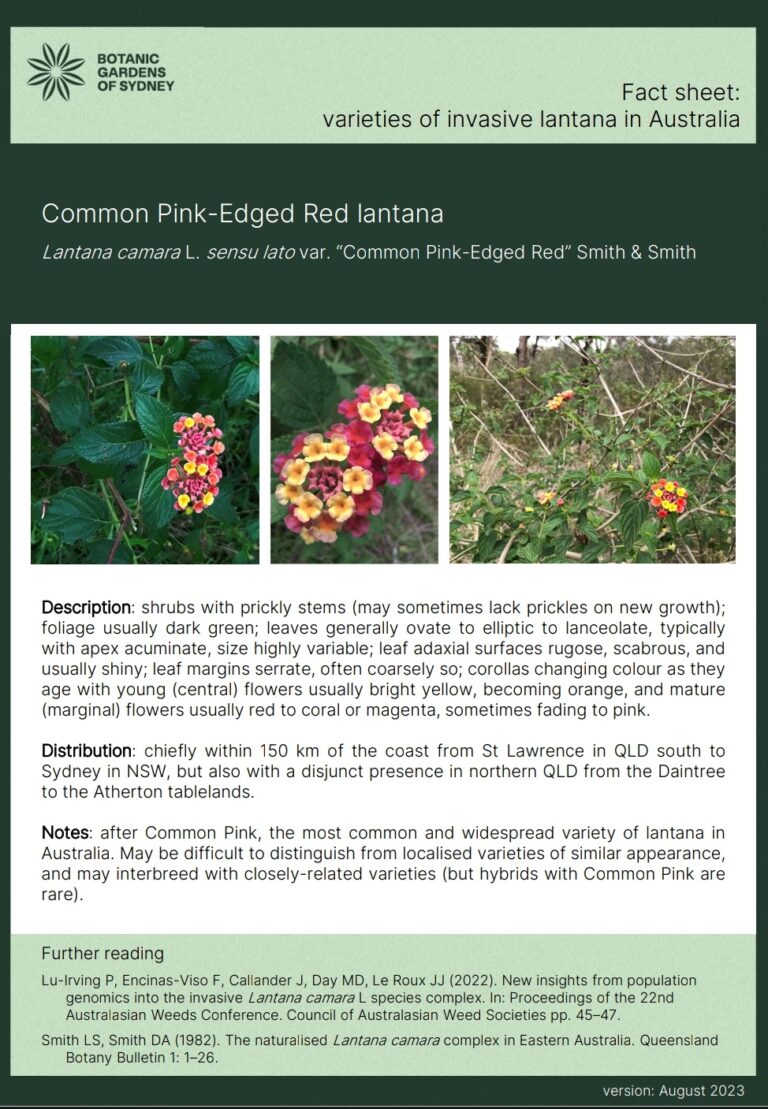

Lantana camara L sensu lato var. “Common Pink-Edged Red”

Revised description following Smith & Smith 1982

Shrubs with prickly stems (may sometimes lack prickles on new growth); foliage usually dark green; leaves generally ovate to elliptic to lanceolate, often with apex acuminate, size highly variable; leaf upper surfaces rugose, scabrous, and usually shiny; leaf margins serrate, often moderately coarsely so; corollas changing colour as they age with young (central) flowers usually bright yellow, becoming orange, and mature (marginal) flowers usually red to coral or magenta, sometimes fading to pink; distributed chiefly within 150 km of the coast from St Lawrence in QLD south to Sydney in NSW, but also with a disjunct presence in northern QLD from the Daintree to the Atherton tablelands.

Download fact sheets for Australia's most common Lantana varieties:

How to make the most of lantana biocontrol in Australia

There are currently 19 biocontrol agents established on lantana in Australia, with another two in the process of being evaluated for potential release. Of these agents, most are thought to have reached their full potential distribution and effect. However, their populations may fluctuate seasonally, and migrate in response to turnover and shift in lantana host populations. A few, more recently introduced agents might still have the potential to affect a larger range than they currently occupy. The following agents are considered to be the most relevant because they are among the most widespread, damaging, and/or promising (yet to reach their full effect).

Uroplata girardi

Octotoma scabripennis

Teleonemia scrupulosa

Aconophora compressa

Prospodium tuberculatum

Aceria lantanae